UCSF researchers discover that oestrogen can turn on pain signals associated with conditions like irritable bowel syndrome.

Women are dramatically more likely than men to suffer from irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), a chronic condition causing abdominal pain, bloating, and digestive discomfort. Now, scientists at UC San Francisco have discovered why.

Oestrogen, the researchers report in Science, activates previously unknown pathways in the colon that can trigger pain and make the female gut more sensitive to certain foods and their breakdown products. When male mice were given oestrogen to mimic the levels found in females, their gut pain sensitivity increased to match that of females.

The findings not only explain the female predominance in gut pain disorders but also point to potential new ways to treat the conditions.

“Instead of just saying young women suffer from IBS, we wanted rigorous science explaining why,” said Holly Ingraham, PhD, professor UCSF and co-senior author of the study. “We’ve answered that question, and in the process identified new potential drug targets.”

The research also suggests why low-FODMAP diets – which eliminate certain fermentable foods, such as onions, garlic, honey, wheat, and beans – help some IBS patients, and why women’s gut symptoms often fluctuate with their menstrual cycles.

“We knew the gut has a sophisticated pain-sensing system, but this study reveals how hormones can dial that sensitivity up by tapping into this system through an interesting and potent cellular connection,” said co-senior author David Julius, PhD. Julius won the 2021 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for his work on pain sensation.

Search for oestrogen

Previous research had hinted that oestrogen was to blame for higher rates of IBS in females, but not why. To understand how oestrogen might be involved, Ingraham’s and Julius’s teams first needed to see exactly where the hormone was working in the gut.

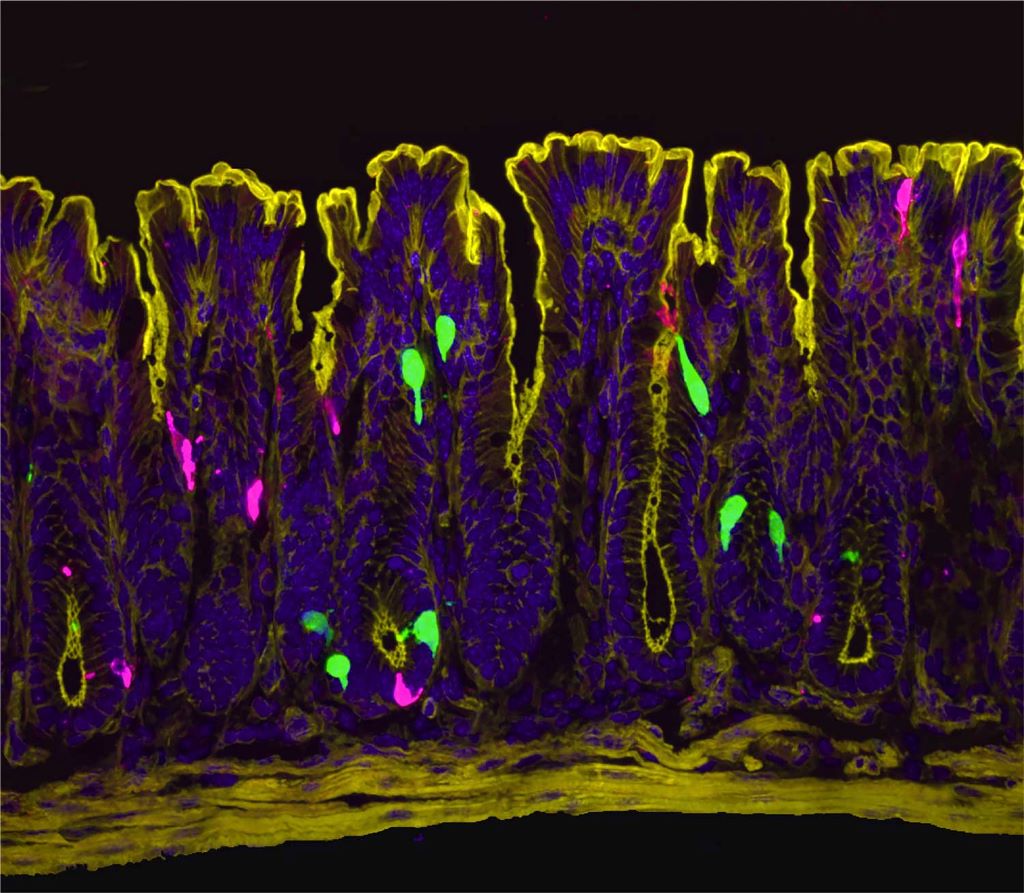

“At the time I started this project, we didn’t know where and how oestrogen signalling is set up in the female intestine,” said Archana Venkataraman, PhD, a postdoc in Ingraham’s lab and co-first author of the research. “So, our initial step was to visualise the oestrogen receptor along the length of the female gut.”

The team expected to see oestrogen receptors in enterochromaffin (EC) cells, which were already known to send pain signals from the gut to the spinal cord. Instead, they got a surprise: oestrogen receptors were clustered in the lower part of the colon and in a different cell type known as L-cells.

The scientists pieced together a complex chain reaction that occurs when oestrogen binds to the L-cells. First, oestrogen causes L-cells to release a hormone called PYY (peptide YY). PYY then acts on neighbouring EC cells, triggering them to release the neurotransmitter serotonin, which activates pain-sensing nerve fibres. In female mice, removing the ovaries or blocking oestrogen, serotonin, or PYY dramatically reduced the high gut pain observed in females.

For decades, scientists believed PYY primarily suppressed appetite – drug companies even tried developing it as a weight-loss medication. But those clinical trials failed due to a troubling side effect that was never fully explained; participants experienced severe gut distress. The new findings mesh with this observation and suggest a completely new role for PYY.

“PYY had never been directly described as a pain signal in the past,” said co-first author Eric Figueroa, PhD, a postdoc in Julius’ lab. “Establishing this new role for PYY in gut pain reframes our thinking about this hormone and its local effects in the colon.”

This video shows what happens to the enterochromaffin (EC) cells in the colon when they are treated with PYY. Upon PYY treatment, calcium activity increases in the EC cell, causing it to fluoresce more brightly as it releases serotonin that is detected by nearby pain-sensing nerve fibres. Video by Eric Figueroa/UCSF

A link between IBS and diet

Increased PYY wasn’t the only way that L-cells responded to oestrogen. Levels of another molecule, called Olfr78, also went up in response to the hormone. Olfr78 detects short-chain fatty acids – metabolites produced when gut bacteria digest certain foods. With more Olfr78 receptors, L-cells become hypersensitive to these fatty acids and are more easily triggered to become active, releasing more PYY.

“It means that oestrogen is really leading to this double hit,” said Venkataraman. “First it’s increasing the baseline sensitivity of the gut by increasing PYY, and then it’s also making L-cells more sensitive to these metabolites that are floating around in the colon.”

The observation may explain why low-FODMAP diets help some IBS patients. FODMAPs (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols) are carbohydrates that gut bacteria ferment into those same fatty acids sensed by Olfr78. By eating fewer FODMAPs, patients may be preventing the activation of Olfr78, and, in turn, keeping L-cells from churning out more of the pain signalling PYY.

While men have this same cellular pathway, their lower oestrogen levels keep it relatively quiet. However, the pathway could engage in men taking androgen-blocking medications, which block the effects of testosterone and can elevate oestrogen in some cases, potentially leading to digestive side-effects.

The new work suggests potential ways to treat IBS in women and men alike.

“Even for patients who see success with a low-FODMAP diet, it’s nearly impossible to stick to long term,” Ingraham said. “But the pathways we’ve identified here might be leveraged as new drug targets.”

The researchers are now studying how such drugs might work, as well as asking questions about what other hormones, such as progesterone, might play a role in gut sensitivity and how pregnancy, lactation, and normal menstrual cycles affect intestinal function.

By Sarah C.P. Williams