Finding a way to replicate the skin’s complicated dermis layer has long been a goal of healing burn wounds, as it would greatly reduce scarring and restore functionality. Researchers at Linköping University have developed a gel containing living cells that can be 3D-printed onto a transplant, which then sticks to the wound and creates a scaffold for the dermis to grow.

Large burns are often treated by transplanting a thin layer of the top part of the skin, the epidermis, which is basically composed of a single cell type. Transplanting only this part of the skin leads to severe scarring.

“Skin in a syringe”

Beneath the epidermis is the dermis, which has the blood vessels, nerves, hair follicles and other structures necessary for skin function and elasticity. However, transplanting also the dermis is rarely an option, as the procedure leaves a wound as large as the wound to be healed. The trick is to create new skin that does not become scar tissue but a functioning dermis.

“The dermis is so complicated that we can’t grow it in a lab. We don’t even know what all its components are. That’s why we, and many others, think that we could possibly transplant the building blocks and then let the body make the dermis itself,” says Johan Junker, researcher at the Swedish Center for Disaster Medicine and Traumatology and docent in plastic surgery at Linköping University, who led the study published in Advanced Healthcare Materials.

The most common cell type in the dermis, the connective tissue cell or fibroblast, is easy to remove from the body and grow in a lab. The connective tissue cell also has the advantage of being able to develop into more specialised cell types depending on what is needed. The researchers behind the study provide a scaffold by having the cells grow on tiny, porous beads of gelatine, a substance similar to skin collagen. But a liquid containing these beads poured on a wound will not stay there.

The researchers’ solution to the problem is mixing the gelatine beads with a gel consisting of another body-specific substance, hyaluronic acid. When the beads and gel are mixed, they are connected using what is known as click chemistry. The result is a gel that, somewhat simplified, can be called skin in a syringe.

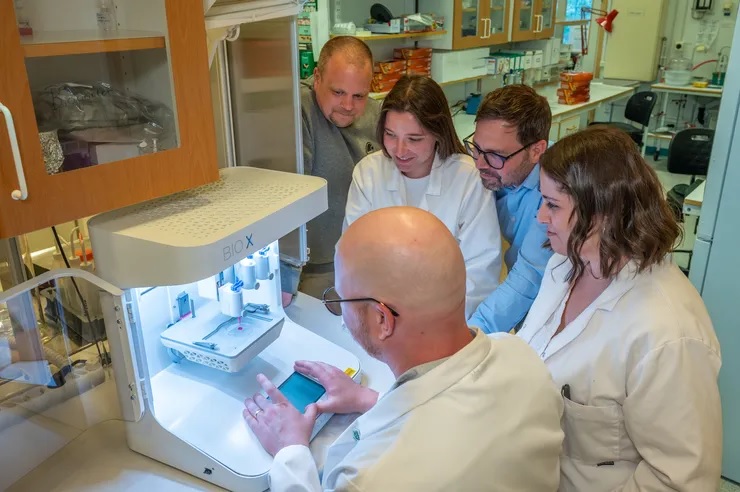

“The gel has a special feature that means that it becomes liquid when exposed to light pressure. You can use a syringe to apply it to a wound, for example, and once applied it becomes gel-like again. This also makes it possible to 3D print the gel with the cells in it,” says Daniel Aili, professor of molecular physics at Linköping University, who led the study together with Johan Junker.

3D-printed transplant

In the current study, the researchers 3D-printed small pucks that were placed under the skin of mice. The results point to the potential of this technology to be used to grow the patient’s own cells from a minimal skin biopsy, which are then 3D-printed into a graft and applied to the wound.

“We see that the cells survive and it’s clear that they produce different substances that are needed to create new dermis. In addition, blood vessels are formed in the grafts, which is important for the tissue to survive in the body. We find this material very promising,” says Johan Junker.

Blood vessels are key to a variety of applications for engineered tissue-like materials. Scientists can grow cells in three-dimensional materials that can be used to build organoids. But there is a bottleneck as concerns these tissue models; they lack blood vessels to transport oxygen and nutrients to the cells. This means that there is a limit to how large the structures can get before the cells at the centre die from oxygen and nutrient deficiency.

Step towards labgrown blood vessels

The LiU researchers may be one step closer to solving the problem of blood vessel supply. In another article, also published in Advanced Healthcare Materials, the researchers describe a method for making threads from materials consisting of 98 per cent water, known as hydrogels.

“The hydrogel threads become quite elastic, so we can tie knots on them. We also show that they can be formed into mini-tubes, which we can pump fluid through or have blood vessel cells grow in,” says Daniel Aili.

The mini-tubes, or the perfusable channels as the researchers also call them, open up new possibilities for the development of blood vessels for eg, organoids.

Source: Linköping University