World’s First Pig-to-Human Liver Xenotransplant in a Living Recipient

Research in the Journal of Hepatology demonstrates that genetically engineered porcine livers can support key hepatic functions in humans

An important new study in the Journal of Hepatology, published by Elsevier, reports the world’s first auxiliary liver xenotransplant from a genetically engineered pig to a living human recipient. The patient survived for 171 days, offering proof-of-concept that genetically modified porcine livers can support key metabolic and synthetic functions in humans, while also underscoring the complications that currently limit long-term outcomes.

According to the World Health Organization, thousands of patients die every year while waiting for organ transplants due to the limited supply of human organs. In China alone, hundreds of thousands experience liver failure annually, yet only around 6000 people received a liver transplant in 2022. This pioneering case offers a potential new avenue to bridge the gap between organ demand and availability.

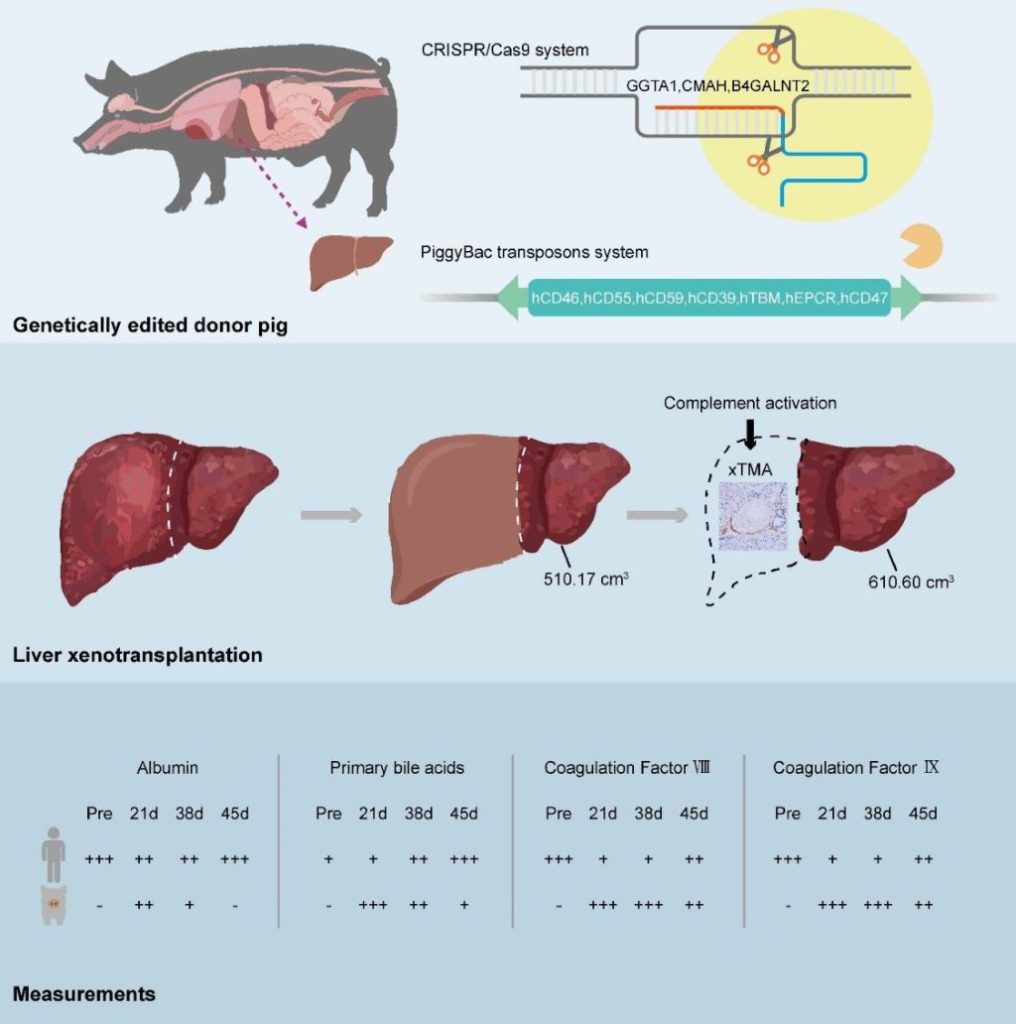

The case involved a 71-year-old man with hepatitis B-related cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma who was not eligible for resection or human liver transplantation. Surgeons implanted an auxiliary graft from a genetically modified Diannan miniature pig with 10 gene edits, including xenoantigen knockouts and human transgenes to enhance immune and coagulation compatibility.

For the first month after surgery, the graft functioned effectively, producing bile and synthesising coagulation factors, with no evidence of hyperacute or acute rejection. However, on day 38, the graft was removed following the development of xenotransplantation-associated thrombotic microangiopathy (xTMA), a serious complication related to complement activation and endothelial injury. Treatment with the complement inhibitor eculizumab and plasma exchange successfully resolved the xTMA. Despite this, the patient later experienced repeated episodes of upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage and passed away on day 171.

“This case proves that a genetically engineered pig liver can function in a human for an extended period,” explained lead investigator Beicheng Sun, MD, PhD, Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery, and President of the First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, Hefei, Anhui Province, China. “It is a pivotal step forward, demonstrating both the promise and the remaining hurdles, particularly regarding coagulation dysregulation and immune complications, that must be overcome.”

“This report is a landmark in hepatology,” commented Heiner Wedemeyer, MD, Co-Editor, Journal of Hepatology, and Department. of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, Infectious Diseases and Endocrinology, Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany, in an accompanying editorial. “It shows that a genetically modified porcine liver can engraft and deliver key hepatic functions in a human recipient. At the same time, it highlights the biological and ethical challenges that remain before such approaches can be translated into wider clinical use. Xenotransplantation may open completely new paths for patients with acute liver failure, acute-on-chronic liver failure, and hepatocellular carcinoma. A new era of transplant hepatology has started.”

“The publication of this case reaffirms the Journal of Hepatology as the world’s leading liver journal. We are committed to presenting cutting-edge translational discoveries that redefine what is possible in hepatology,” added Vlad Ratziu, MD, PhD, Editor in Chief, Journal of Hepatology, and Institute for Cardiometabolism and Nutrition, Sorbonne Université and Hospital Pitié Salpêtrière, Paris, France.