Microprotein Plays Vital Role in Fat Accumulation

Findings could lead to new treatments to improve metabolic health and reduce risks of obesity, diabetes

A microprotein called adipogenin appears to play a key role in helping fat cells store lipid droplets – a phenomenon that’s pivotal for metabolic health, a study co-led by UT Southwestern Medical Center researchers shows. The findings, published in Science, could lead to new strategies to improve healthy lipid storage, which in turn may reduce risks of obesity, diabetes, and other metabolic conditions.

“This study builds upon our long-standing interest in how fat cells maintain their cellular health upon expansion. We show that a tiny microprotein punches far above its weight in sculpting fat biology,” said Philipp Scherer, PhD, Professor of Internal Medicine and Cell Biology and Director of the Touchstone Center for Diabetes Research at UT Southwestern.

Dr Scherer led the study with co-first authors Chao Li, PhD, and Xue-Nan Sun, PhD, Instructors of Internal Medicine at UTSW, and co-senior author Elina Ikonen, MD, PhD, Professor of Anatomy at the University of Helsinki.

After every meal, Dr Scherer explained, any lipids that aren’t burned immediately for energy must be stored in the body. The most common and healthy place to store lipids is in fat cells, or adipocytes, which stockpile these nutrients as droplets, much like oil forms droplets in water. Lipids stored in other cell types can cause a condition called lipotoxicity, spurring cell damage and cell death.

Previous research at UTSW and elsewhere has shown that a protein called seipin is critical for healthy lipid storage in a diverse range of organisms, including plants, fungi, and mammals. But how seipin accomplishes this feat has been unclear. Some studies have suggested that adipogenin – a small protein made of only 80 amino acids as compared with the hundreds found in seipin – is also important for lipid storage, but its exact function was unknown.

To answer these questions, the researchers isolated adipogenin along with its interacting proteins from mice, which produce a form of this microprotein that’s nearly identical to the one in humans. The most common binding partner for adipogenin turned out to be seipin.

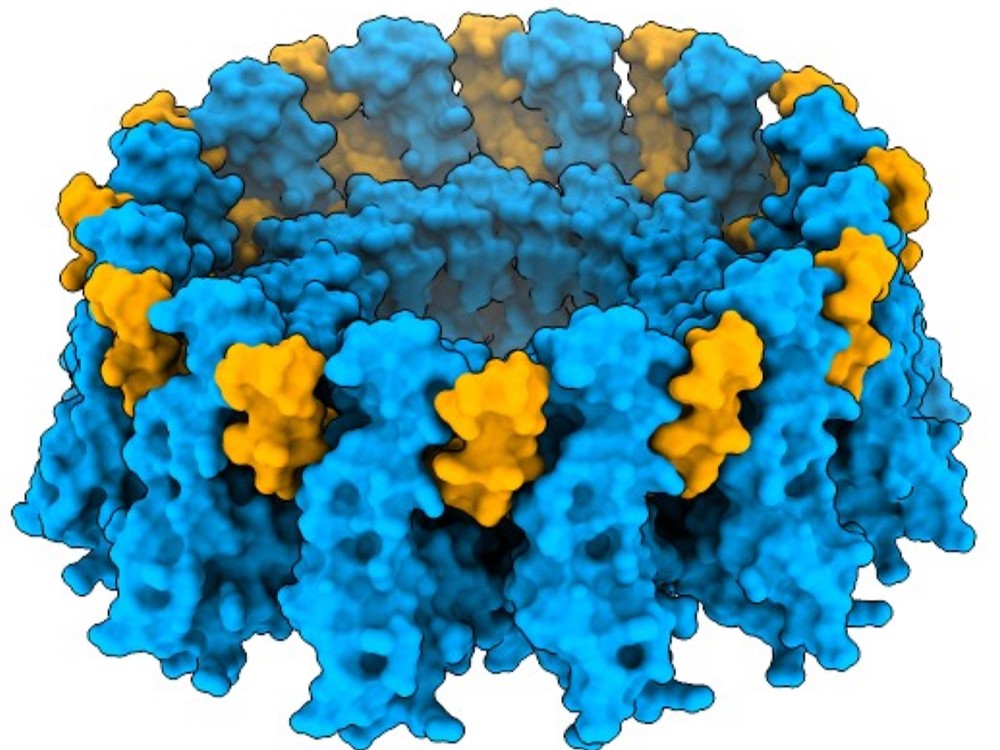

Using cryo-electron microscopy, a technique that can image molecules at the atomic level, researchers showed that adipogenin appeared to reinforce seipin’s structure, making it more rigid and stable. Working with mouse models that overproduced adipogenin, the scientists found that their fat cells held significantly larger lipid droplets. They also stored considerably more fat than unaltered mice. In contrast, mouse models that produced no adipogenin had much smaller lipid droplets in their fat cells and less fat overall.

“This study nudges us a little closer to the clinic by revealing a brand-new handle on how fat cells store lipids, which matters enormously for obesity, diabetes, lipodystrophy, and fatty liver disease,” Dr Scherer said. “Adipogenin becomes a druggable lever on seipin’s machinery, with the promise to either dampen harmful fat buildup or boost healthy adipose storage when needed.”

Source: UT Southwestern Medical Center