Link Between High Cholesterol and Breast Cancer Explained

While chronically high cholesterol levels are linked to increased risks of breast cancer and worse outcomes in most cancers, the link had not been fully understood until now.

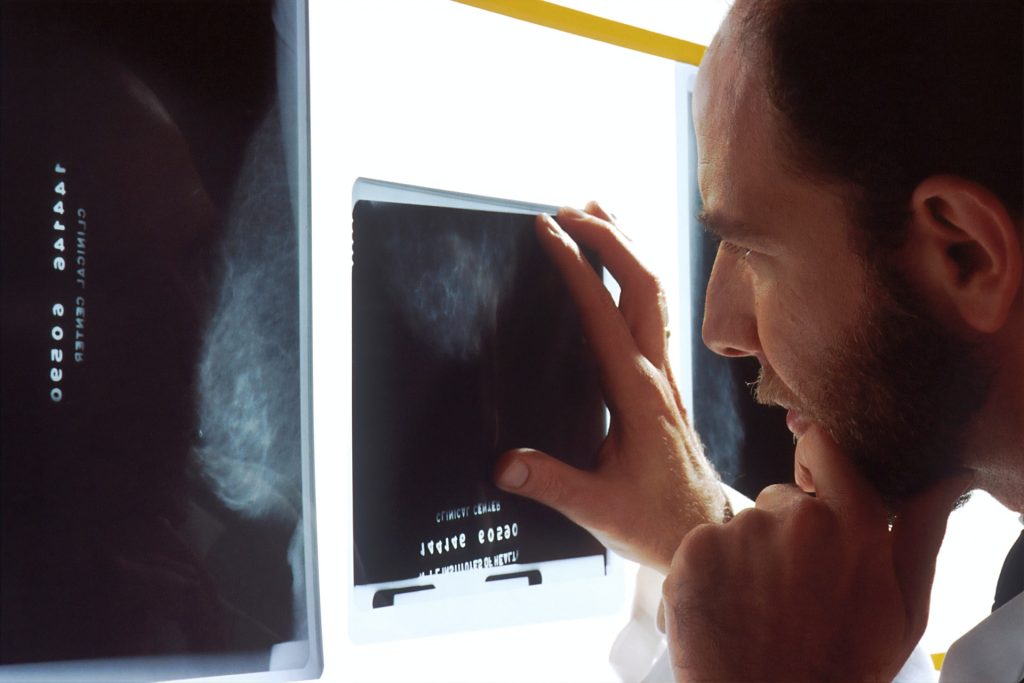

In a study published in Nature Communications, researchers identify the mechanisms at work, describing how breast cancer cells utilise cholesterol to develop stress tolerance, preventing them from dying as they migrate from the original tumour site.

“Most cancer cells die as they try to metastasise – it’s a very stressful process,” said senior author Donald P. McDonnell, Ph.D., professor in the departments of Pharmacology and Cancer Biology and Medicine at Duke University School of Medicine. “The few that don’t die have this ability to overcome the cell’s stress-induced death mechanism. We found that cholesterol was integral in fueling this ability.”

McDonnell and colleagues built on earlier research in their lab focusing on the link between high cholesterol and oestrogen-positive breast and gynaecological cancers. Those studies found that cancers fueled by the oestrogen hormone benefitted from derivatives of cholesterol that act like oestrogen, stoking cancer growth.

But a paradox emerged for estrogen-negative breast cancers. These cancers are not oestrogen dependent, but high cholesterol is still associated with worse disease, which indicates the possible effect of a different mechanism.

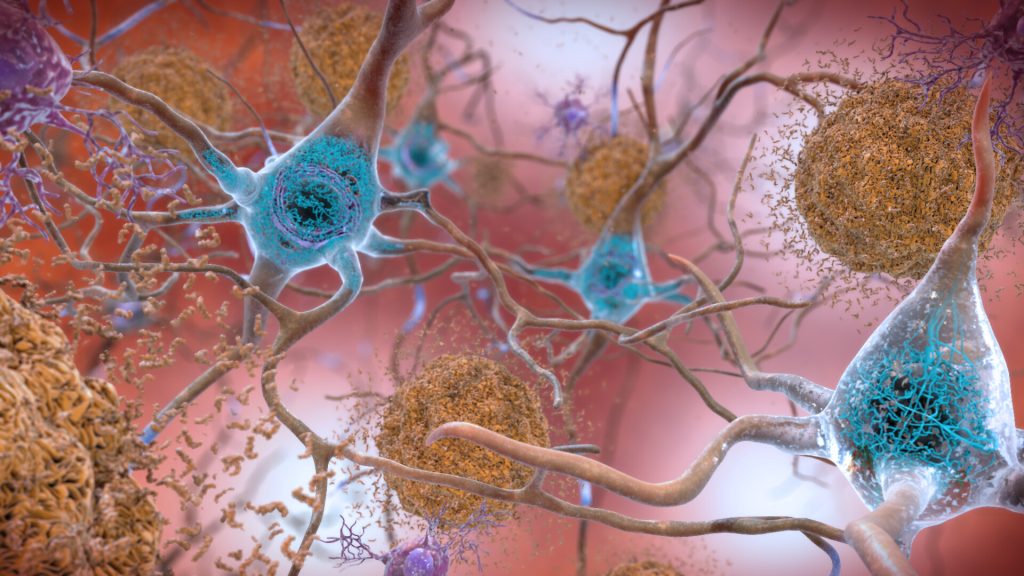

In the current study using cancer cell lines and mouse models, the Duke researchers found that migrating cancer cells gobble cholesterol in response to stress. Most die.

However, those that live emerge with a super-power that makes them able to withstand ferroptosis, a natural process in which cells succumb to stress. These stress-impervious cancer cells then proliferate and readily metastasise.

Other tumours beside ER-negative breast cancer cells use this process. including melanoma. And the mechanisms identified could be targeted by therapies.

“Unraveling this pathway has highlighted new approaches that may be useful for the treatment of advanced disease,” McDonnell said. “There are contemporary therapies under development that inhibit the pathway we’ve described. Importantly, these findings yet again highlight why lowering cholesterol — either using drugs or by dietary modification — is a good idea for better health.”

Source: Duke University