Elevated Risk of Death or Complications from Broken Heart Syndrome

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, also known as broken heart syndrome, is associated with a high rate of death and complications, and those rates were unchanged between 2016 and 2020, according to new research published in the Journal of the American Heart Association, an open-access, peer-reviewed journal of the American Heart Association.

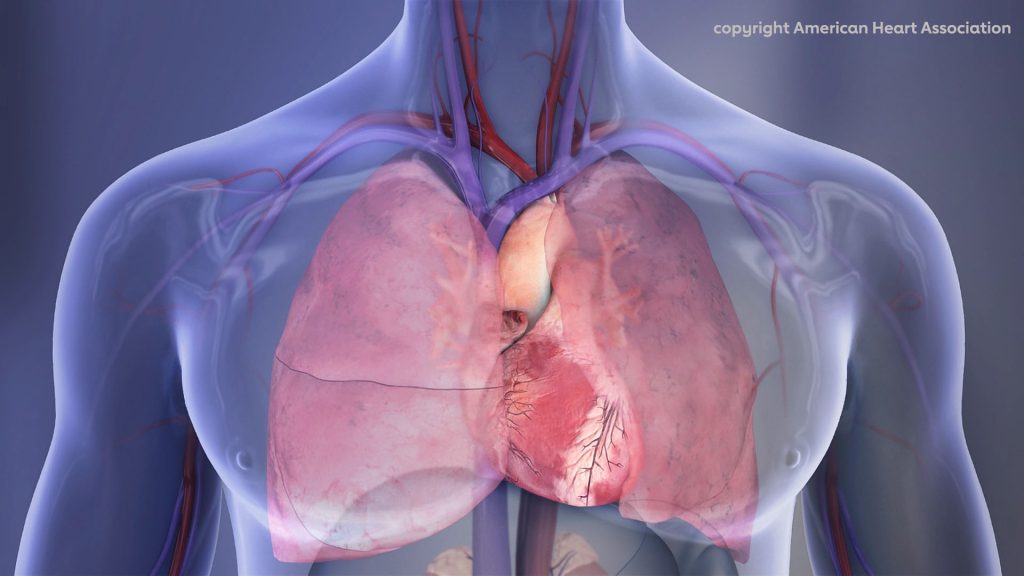

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is a stress-related heart condition in which part of the heart temporarily enlarges and doesn’t pump well. It is thought to be a reaction to a surge of stress hormones that can be caused by an emotionally or physically stressful event, such as the death of a loved one or a divorce. It can lead to severe, short-term failure of the heart muscle and can be fatal. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy may be misdiagnosed as a heart attack because the symptoms and test results are similar.

This study is one of the largest to assess in-hospital death rates and complications of the condition, as well as differences by sex, age and race over five years.

“We were surprised to find that the death rate from Takotsubo cardiomyopathy was relatively high without significant changes over the five-year study, and the rate of in-hospital complications also was elevated,” said study author M. Reza Movahed, MD, PhD, an interventional cardiologist and clinical professor of medicine at the University of Arizona’s Sarver Heart Center in Tucson, Arizona. “The continued high death rate is alarming, suggesting that more research be done for better treatment and finding new therapeutic approaches to this condition.”

Researchers reviewed health records in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database to identify people diagnosed with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy from 2016 to 2020.

The analysis found:

- The death rate was considered high at 6.5%, with no improvement over period.

- Deaths were more than double in men at 11.2% compared to the rate of 5.5% among women.

- Major complications included congestive heart failure (35.9%), atrial fibrillation (20.7%), cardiogenic shock (6.6%), stroke (5.3%) and cardiac arrest (3.4%).

- People older than age 61 had the highest incidence rates of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. However, there was a 2.6 to 3.25 times higher incidence of this condition among adults ages 46-60 compared to those ages 31-45 during the study period.

- White adults had the highest rate of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (0.16%), followed by Native American adults (0.13%) and Black adults (0.07%).

- In addition, socioeconomic factors, including median household income, hospital size and health insurance status, varied significantly.

“Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is a serious condition with a substantial risk of death and severe complications,” Movahed said. “The health care team needs to carefully review coronary angiograms that show no significant coronary disease with classic appearance of left ventricular motion, suggesting any subtypes of stress-induced cardiomyopathy. These patients should be monitored for serious complications and treated promptly. Some complications, such as embolic stroke, may be preventable with an early initiation of anti-clotting medications in patients with a substantially weakened heart muscle or with an irregular heart rhythm called atrial fibrillation that increases the risk of stroke.”

He also noted that age-related findings could serve as a useful diagnostic tool in discriminating between heart attack/chest pain and Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, which may prompt earlier diagnosis of the condition and could also remove assumptions that Takotsubo cardiomyopathy only occurs in the elderly.

Among the study’s limitations is that it relied on data from hospital codes, which could have errors or overcount patients hospitalized more than once or transferred to another hospital. In addition, there was no information on outpatient data, different types of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy or other conditions that may have contributed to patients’ deaths.

Movahed said further research is needed about the management of patients with Takotsubo cardiomyopathy and the reason behind differences in death rates between men and women.

Source: American Heart Association